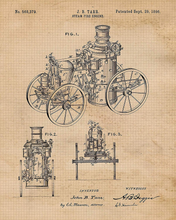

Historic J.B Tarr patent of a Steam fire engine engraved leather patch hat, Industrially sewn on by hand to ensure the highest quality!

Adjustable size- 6 3/8 (51cm) to 8 (64cm)

Custom logos or designs are always available under our design your own engraved products, Design your own leather patch hats online here, Patches are engraved and sewn on, and patch options will be round, oval, and rectangular.

"Get Inspired" with JTM VINTAGE  ®

®

History facts:

Early Steam Fire Engines

To John Braithwaite goes the credit for the first steam engine intended for the purpose of putting out fires. Braithwaite, a London steam train pioneer, had built the "Novelty," the first locomotive to travel a mile in under a minute. In 1829 he constructed the first practical steam fire engine (pictured right), which moved less than a gallon of water per minute and took 20 minutes to get up steam. London’s fire brigades did not care for the new engine and it was eventually destroyed by an angry mob.

The first steam fire engine built in America (pictured left) was made by Paul Rapsey Hodge in New York City in 1841. Remarkably, it was self-propelled and harness steam both for moving water and moving itself. As in London, New York's firefighters were resistant to the new technology and abandoned use of Hodge’s engine after only a few months.

Alexander “Moses” Latta has the distinction of making the first practical steam fire engine regularly used by a city fire department. In 1852, Latta’s experimental engine was tested before Cincinnati’s City Council and proved itself capable of raising steam in just over four minutes (quite an improvement over Braithwaite’s 20 minute time 23 years earlier) and spraying water 130 feet. The City Council commissioned Latta to build such an engine for Cincinnati and the “Uncle Joe Ross” (pictured right), named for the Councilman who promoted the engine, was delivered in 1853. It was manned by Cincinnati’s newly organized paid department, which replaced the city's volunteers. “Uncle Joe Ross” was cumbersome at 22,000 pounds and, despite being "self-propelled,” still required four horses to pull it. It exploded at a trial in 1855.

The first trial of a steam fire engine in Baltimore was of the “Miles Greenwood” in 1855. This engine was of the Latta design and had been built in Cincinnati. The trial convinced the First Baltimore Hose Company to purchase the steam fire engine “Alpha” in 1858. Coincidentally, as in Cincinnati, this purchase came at a time of change for firefighters in Baltimore. In 1859, Baltimore transitioned from a firefighting force of 22 volunteer companies to a paid department of nine companies. In addition to the First Baltimore Hose Company, the Washington Hose Company, Vigilant Company, and the Mechanical Fire Engine Company each bought steam fire engines in 1858, not realizing the coming change. These steamers were then bought out by the new Baltimore City Fire Department in 1859.

The transition to paid departments was a trend that spread across the country beginning with Cincinnati in 1852.

THE CURIOUS (AND EXPLOSIVE) HISTORY OF CINCINNATI’S FIRST STEAM FIRE ENGINE

Cincinnati’s wonderful Fire Museum on Court Street continually burnishes our city’s two fire-fighting claims to fame: Cincinnati created the first professional fire department in the United States in 1853, and Cincinnati craftsmen invented the first successful steam-powered fire engine in 1852. Those two facts are inextricably connected and they are even mostly true, although they do not tell the whole story.

Usually missing from Cincinnati’s fire-fighting history are a few additional facts that provide clearer context:

Cincinnati had to pay its firefighters to haul the new fire engine to fires because amateurs refused to operate the contraption.

Cincinnati’s steam fire engine was not the first; other inventors had produced steam-powered fire engines decades earlier.

Cincinnati’s first steam-powered fire engine exploded during a public demonstration, killing the operator.

Although Cincinnati created the first professional fire department in 1853, the impetus for this innovation can be traced to a riot between two companies of firefighters in 1851. For decades, Cincinnati’s fire protection had been provided by a couple dozen amateur associations. Whatever company showed up first and extinguished the fire got paid by the insurance company that provided coverage for that particular building. If two or more companies appeared simultaneously, brawls erupted to determine who would get paid. The 1895 History of the Cincinnati Fire Department describes an all-too-common scene:

“One of the fiercest contests occurred in the year 1851. The battle took place during a fire on the corner of Augusta and John streets, between Western Hose Company No. 3, and the Washington Company No. 1. On that occasion ten companies were drawn into the fight, while the building, a planing mill, was permitted to burn to the ground. Mayor [Mark P.] Taylor appeared on the scene and read the riot act, but to no purpose, the battle continuing until daylight.”

Eager as they were to pound one another into the pavement, Cincinnati’s volunteer fire-fighters wanted nothing to do with this steam engine, which could certainly out-perform any of their old-fashioned hand pumpers. William T. King, in his 1896 History of the American Steam Fire Engine explains why:

“As the time approached for the trial of the engine, the volunteer firemen were in a ferment. It would never do to destroy the engine before it had had a trial; and to destroy it after a successful exhibit of its powers was made, would be equally useless. So it was understood that no demonstration, pro or con, would be made on it until it should come to a fire, when it was to be rendered useless and all who had a hand in its working were to be rendered useless also.”

A source described only as “an old-time visitor to Cincinnati” related how he was drafted into driving the first steam engine to a fire because none of the volunteer firemen would go near it:

“We were on our way to church Sunday morning when the fire bells struck, and my brother said: ‘Now we’ll see what they will do with the steam machine,’ and we started for Miles Greenwood’s shop, where the steam fire engine was. It was built by Greenwood, the first ever on wheels. There the engine stood, steam up, four large gray horses hitched to it, a crowd looking at it, and Greenwood as mad as the devil because he couldn’t get a man to drive the horses. You see all the firemen were opposed to this new invention because they believed it would spoil their fun, and nobody wanted to be stoned by them, and then, the horses were kicking about so that everybody was afraid on that account. My brother says: ‘Larry, you can drive those horses, I know.’ And Greenwood said: ‘If you can I wish you would; I’ll pay you for it.’ My business was teaming, you see. And just as I was with my Sunday clothes on, I jumped on the back of a wheel horse, seized the rein, spoke to the horses, and out we went kiting.”

The steam engine in that anecdote was, most likely, the first practical steam-powered fire developed by Alexander Bonner “Moses” Latta and Abel Shawk. Their first functional machine was christened the “Uncle Joe Ross” after the city councilman who introduced legislation to buy the engine for the city. Latta and Shawk were probably aware that other inventors had built steam fire engines in New York and Berlin. Those predecessors proved impracticable, however, because they took too long to build up enough steam to pump water. Latta and Shawk built a machine that could go from ignition to full steam in a little over five minutes, meaning the engine was usually ready to pump by the time it arrived at the fire.

Cincinnati’s innovative professional fire department and high-tech steam engines attracted visitors from all over the country. On December 5, 1855, a delegation from Chicago traveled to the Queen City to study how this new-fangled system worked in practice. To show off the new toys, a pumping demonstration was arranged that afternoon at the intersection of Sixth and Vine, with two pumpers, the Uncle Joe Ross and the A.B. Latta, named for its inventor.

The Latta showed up first, under the supervision of Mr. Latta himself, but took an unusually long time—almost 12 minutes—to get up a good head of steam. As it was puffing along, the Uncle Joe Ross pulled into the intersection, operated by British-born and high-strung John Winterbottom, who decided to prove he knew more about steam than the celebrated inventor himself. In just seven minutes, the Uncle Joe Ross built enough steam to throw two streams of water hundreds of feet in the air.

Latta told Winterbottom that his engine did not have enough water in the boiler. Winterbottom responded with a suggestion that Latta perform an anatomically impossible act. Just as Winterbottom’s engine reached a peak pressure of 180 pounds per square inch—normal operating pressure was just 60 psi—the hose on Latta’s engine ruptured and the crowd lurched backward. This retreat saved several lives because, at that moment, the Uncle Joe Ross exploded, spraying steam and shrapnel. According to the Cincinnati Railroad Record [13 December 1855]:

“The engineer, John Winterbottom, was blown into the air a considerable height, and fell some fifty yards from the engine. His legs were blown from the body, the entrails of which were torn out, and when picked up, nothing but the trunk and head remained. It was a sickening sight, and will not be readily forgotten by those who witnessed it.”

Despite the potential for accidents, steam-powered fire engines remained the standard for fire departments throughout the United States for the next 60 years. The company founded by Latta and Shawk evolved, over the years, into the Ahrens-Fox Company, producers of vehicles long considered the pinnacle of classic fire engines.